Week 9 Monday

Contents

Week 9 Monday#

Announcements#

Online Quiz 6 is available. See Friday’s notebook and my Canvas message for more details.

I have office hours after class today at 11am, next door in ALP 3610.

Worksheets due by 11:59pm tomorrow.

Videos and video quizzes posted; due Monday before lecture.

On Wednesday we will discuss the Course Project. Instructions are posted in the course notes. See also the accompanying Worksheet 16.

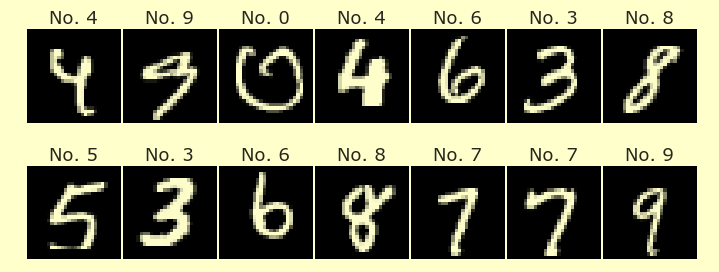

In today’s worksheet, we use a random forest to classify handwritten digits. Take a moment to think about how difficult that would be to do by hand. We are producing a function \(\mathbb{R}^{784} \rightarrow \{0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9\}\).

Simulated data for classification#

We didn’t talk about most of this code during lecture. It is here just to give us some data to work with, data that can be used to show how random forests work.

import pandas as pd

import altair as alt

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X,y = make_blobs(n_samples=500, n_features=2, centers=[[0,0],[2,2]], random_state=13)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X,y, train_size=0.9, random_state=0)

df_true = pd.DataFrame(X, columns=["x","y"])

df_true["Class"] = y

alt.Chart(df_true).mark_circle().encode(

x="x",

y="y",

color="Class:N"

).properties(

title="True values"

)

Here is a helper function that can plot predictions for us.

# clf should already be fit before calling this function

def make_chart(clf, X):

outputs = clf.predict(X)

df = pd.DataFrame(X, columns=["x", "y"])

df["pred"] = outputs

c = alt.Chart(df).mark_circle().encode(

x="x",

y="y",

color="pred:N"

)

return c

Decision trees for the above data#

Plot the predictions for a Decision Tree Classifier with

max_leaf_nodes=3.What is the accuracy on the training data and on the test data? What is the log loss on the training data and on the test data? Use the following:

print(f'''

Train score: {clf.score(X_train, y_train)}

Test score: {clf.score(X_test, y_test)}

Train log loss: {log_loss(y_train, clf.predict_proba(X_train))}

Test log loss: {log_loss(y_test, clf.predict_proba(X_test))}

''')

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

from sklearn.metrics import log_loss

clf = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_leaf_nodes=3)

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

DecisionTreeClassifier(max_leaf_nodes=3)In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

DecisionTreeClassifier(max_leaf_nodes=3)

Notice the linear boundaries here. That is always the case with decision trees, but sometimes there are so many linear boundaries that we can’t actually recognize the boundaries. Here we are using 3 leaf nodes, so there are only 3 regions in the space.

make_chart(clf, X)

Here I’ve added some format specifications :.1% which says to convert a probability like 0.92444444 into a percentage with one decimal point, like 92.4%. It’s very convenient that Python can make those conversions for us.

print(f'''

Train score: {clf.score(X_train, y_train):.1%}

Test score: {clf.score(X_test, y_test):.1%}

Train log loss: {log_loss(y_train, clf.predict_proba(X_train))}

Test log loss: {log_loss(y_test, clf.predict_proba(X_test))}

''')

Train score: 92.4%

Test score: 92.0%

Train log loss: 0.24577489989714546

Test log loss: 0.26162520838554965

Do the same thing with

max_leaf_nodes=28.

What you should imagine here is that this decision tree is more likely to overfit the data (because we are giving the tree so much more flexibility, with the 28 leaf nodes.

clf = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_leaf_nodes=28)

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

DecisionTreeClassifier(max_leaf_nodes=28)In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

DecisionTreeClassifier(max_leaf_nodes=28)

This chart looks almost identical to the true data. Even though the boundaries are linear, some of the regions are so small that we can’t even tell where the boundaries are. (Here we are coloring the true input points. It would also be interesting to color many more random points in this area… then some of the boundaries would be more apparent. That is what we were rushing through at the end of class last Friday.) Because this picture looks pretty complicated, that is evidence of overfitting.

make_chart(clf, X)

Notice how much more these numbers suggest overfitting: the score is significantly better (i.e., larger) on the training set, and the loss is significantly better (i.e., smaller) on the training set. There is no precise meaning here to “significantly better”, but if you compare these numbers to the numbers with 3 leaf nodes, I think you’ll see a big difference.

print(f'''

Train score: {clf.score(X_train, y_train):.1%}

Test score: {clf.score(X_test, y_test):.1%}

Train log loss: {log_loss(y_train, clf.predict_proba(X_train))}

Test log loss: {log_loss(y_test, clf.predict_proba(X_test))}

''')

Train score: 98.9%

Test score: 92.0%

Train log loss: 0.034770278973321876

Test log loss: 2.123777374229206

A random forest for the above data#

A random forest is made up of multiple decision trees; the keyword argument

n_estimatorsdetermins how many trees to use.If we were to fit many trees using the same parameters and data, they would all look very similar. The trick with random forests is that when we call

rfc.fit(X_train, y_train), the individual trees are fit using different samples ofX_trainandy_train(different trees receive different samples).Another source of randomness is to only allow splitting at certain features (columns) at each step. That doesn’t make as much sense with our data, which only has two columns, but for something like handwritten digits, which has 784 columns, it would make more sense, but we won’t use that approach.

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

Random forests take many of the same keyword arguments as decision trees, like max_leaf_nodes, and also some extra arguments. Here we are using n_estimators=1000 to put 1000 trees into this random forest. Each of the decision trees is restricted to having at most 28 leaves. (I would usually use the variable name rfc for “random forest classifier”, but here I am using clf, so that I can use the same f-string code as above.)

clf = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=1000, max_leaf_nodes=28)

Once we have our random forest classifier, we can do fitting and prediction just like for other supervised machine learning models in scikit-learn.

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

RandomForestClassifier(max_leaf_nodes=28, n_estimators=1000)In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

RandomForestClassifier(max_leaf_nodes=28, n_estimators=1000)

Here is the corresponding predictions. Based on this chart alone, I would be worried about overfitting, but we will see below that overfitting has been reduced significantly from the decision tree example.

make_chart(clf, X)

There is still some overfitting, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing, and the numbers are much better than in the decision tree examples.

print(f'''

Train score: {clf.score(X_train, y_train):.1%}

Test score: {clf.score(X_test, y_test):.1%}

Train log loss: {log_loss(y_train, clf.predict_proba(X_train))}

Test log loss: {log_loss(y_test, clf.predict_proba(X_test))}

''')

Train score: 99.8%

Test score: 96.0%

Train log loss: 0.05109014429942453

Test log loss: 0.11127556952266289

It is very impressive that we can get such a good test score and such a good test log loss using decision trees like in the previous section. We have access to these 1000 individual decision trees via the estimators_ attribute.

z = clf.estimators_

type(z)

list

This list contains the 1000 individual decision trees in our random forest.

len(z)

1000

type(z[40])

sklearn.tree._classes.DecisionTreeClassifier

It can be counter-intuitive that our accuracy on the random forest (whose predictions correspond to an average of the predictions for the individual decision trees) can be better than most of the accuracies for the individual trees.

z[40].score(X_test, y_test)

0.92

z[41].score(X_test, y_test)

0.94

Most of the individual trees have an accuracy of less than 96%, but the overall random forest has an accuracy of 96%. Try to make this same sort of list, but using log_loss. I think you will find the same sort of results, that the random forest has a much better (i.e., lower) log loss than most of the individual trees. (I think this distinction will be even more pronounced for log loss than it was for score, because log loss is a more refined measure.)

[clf_tree.score(X_test, y_test) for clf_tree in z[:45]]

[0.92,

0.9,

0.96,

0.9,

0.9,

0.86,

0.9,

0.98,

0.98,

0.92,

0.88,

0.88,

0.84,

0.94,

0.92,

0.92,

0.9,

0.94,

0.88,

0.94,

0.92,

0.92,

0.92,

0.92,

0.88,

0.88,

0.96,

0.92,

0.94,

0.88,

0.92,

0.94,

0.98,

0.92,

0.86,

0.94,

0.96,

0.9,

0.96,

0.9,

0.92,

0.94,

0.92,

0.9,

0.92]